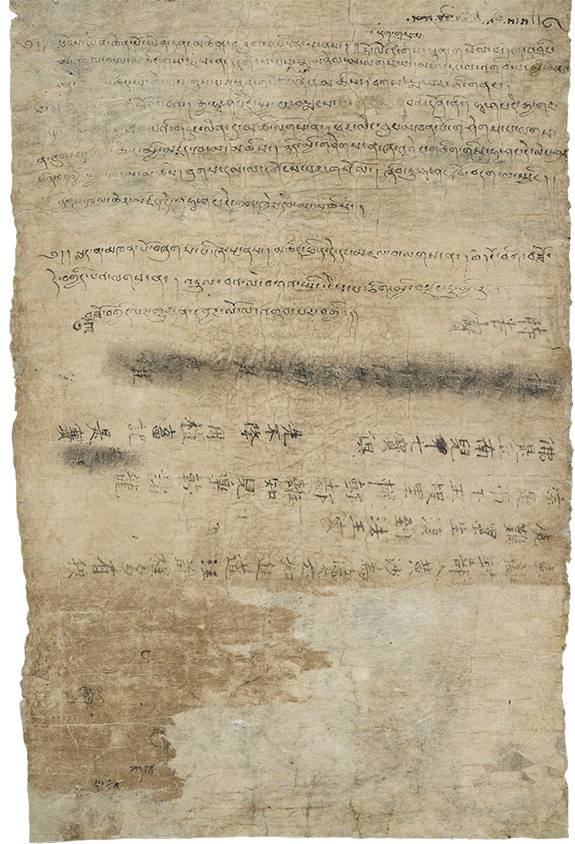

According to Akira Fujieda this was due to the lack of materials for constructing brushes in Dunhuang after the Tibetan occupation in the late 8th century. An unusual feature of the Dunhuang manuscripts dating from the 9th and 10th centuries is that some appear to have been written with a hard stylus rather than with a brush. Most manuscripts, including Buddhist texts, are written in Kaishu or 'regular script', while others are written in the cursive Xingshu or 'running script'.

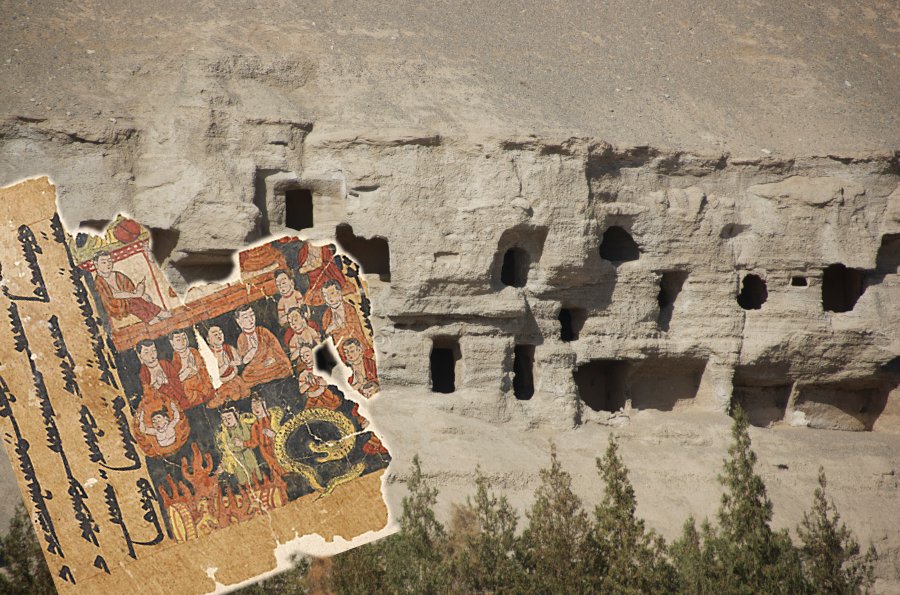

The largest proportion of the manuscripts are written in Chinese, both Classical and, to a lesser extent, vernacular Chinese. The variety of languages and scripts found among the Dunhuang manuscripts is a result of the multicultural nature of the region in the first millennium AD. Liu Bannong compiled Dunhuang Duosuo (敦煌掇瑣 "Miscellaneous works found in the Dunhuang Caves"), a pioneering work about the Dunhuang manuscripts. Even though cave 16 could easily have been enlarged or extended to cave 17, Yoshiro Imaeda has suggested cave 16 was sealed because it ran out of room. A popular hypothesis, first suggest by Paul Pelliot, is that the cave was sealed to protect the manuscripts at the advent of an invasion by the Xixia army, and later scholars followed with the alternative suggestion that it was sealed in fear of an invasion by Islamic Kharkhanids that never occurred.

The reason for the cave's sealing has also been the subject of speculation. More recently, it has been suggested that the cave functioned as a storeroom for a Buddhist monastic library, though this has been disputed. Aurel Stein suggested that the manuscripts were "sacred waste", an explanation that found favour with later scholars including Fujieda Akira. Various reasons have been suggested for the placing of the manuscripts in the library cave and its sealing. While most studies use Dunhuang manuscripts to address issues in areas such as history and religious studies, some have addressed questions about the provenance and materiality of the manuscripts themselves. All of the manuscript collections are being digitized by the International Dunhuang Project, and can be freely accessed online. Those purchased by Western scholars are now kept in institutions all over the world, such as the British Library and the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Rumours of caches of documents taken by local people continued for some time, and a cache of documents hidden by Wang from the authorities was later found in the 1940s. Several thousands of folios of Tibetan manuscripts were left in Dunhuang and are now located in several museums and libraries in the region. Due to the efforts of the scholar and antiquarian Luo Zhenyu, most of the remaining Chinese manuscripts were taken to Beijing in 1910 and are now in the National Library of China. Scholars in Beijing were alerted to the significance of the manuscripts after seeing samples of the documents in Pelliot's possession. Paul Pelliot examining manuscripts in the Library Cave, 1908 Hundreds more of the manuscripts were sold by Wang to Otani Kozui and Sergey Oldenburg. Many of these manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest whereby papers were reused and Buddhist texts were written on the opposite side of the paper. Pelliot was interested in the more unusual and exotic of the Dunhuang manuscripts, such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups.

Pelliot took almost 10,000 documents for the equivalent of £90, but, unlike Stein, Pelliot was a trained sinologist literate in Chinese, and he was allowed to examine the manuscripts freely, so he was able to pick a better selection of documents than Stein. Stein had the first pick and he was able to collect around 7,000 complete manuscripts and 6,000 fragments for which he paid £130, although these include many duplicate copies of the Diamond and Lotus Sutras. The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in. Heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest's little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. Image of Cave 16 taken by Aurel Stein in 1907, with manuscripts piled up beside the entrance to Cave 17, the Library Cave, which is to the right in this picture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)